Spiral Bound

21st May 2013 | 0 Comment(s) | The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences

Cambridge University’s Faculty of Education engage Early Years and Primary PGCE trainee teachers with a range of settings for learning other than school. Helen Davidson spent the last week of her training in museums and was inspired by meeting Thresholds poet Matthew Hollis at the Sedgwick Museum.

Having spent the last week of my PGCE Primary training on a whirlwind tour of various Cambridge museums – mainly the Fitzwilliam – I find myself spellbound and tongue-tied. More than this, I am ‘spiral bound’. The title is ironic, at least in part, because I find the idea of a neatly-presented, coherent write-up of the week, at this stage, completely unthinkable! More importantly, however, it gestures towards the nature of any museum experience. It is not a neat linear progression: ‘ah, now I understand museums and how to use them with children’. Rather, idea connects to idea and before you know it your reflections spiral, often inward, in an attempt to understand and develop a deeper personal connection with the artefacts. By ‘spiral bound’, then, I mean that I am inevitably drawn into a journey of forging connections, but also simply fascinated by the perpetual draw of real objects, natural and human-created artefacts. So, I shall flick through my spiral-bound sketch book and share a sample of my impressions of the week…

As an English graduate, I begin with a poem, Louis Macneice’s ‘The British Museum Reading Room’. Although the line ‘Some are too much alive and some are asleep’ might seem the most appropriate to a school trip to the museum, the children I saw were ‘Folded up in themselves in a world which is safe and silent’. This hints at the overarching tension lying at the heart of all of the Cambridge museums I visited this week: their very silence has a powerful sort of voice and children entering this space are given the opportunity, in this ‘safe and silent’ world, to find their own voices.

On Monday, my fellow trainee, Peter, and I spent the day roaming around various museum settings. We visited the Museum of Cambridge (was Folk Museum) and spent the morning exploring social history in a 17th century timber-framed building which spent many years as an inn. This collection, being formed almost entirely of everyday objects, finds its source in a deep human need to share stories about our experiences. It is easy to see how this museum makes connections with the children’s own lives and can offer them a wonderfully active and tactile experience of the past that is contextually embedded. The starkness of the Museum of Classical Archaeology by comparison highlights an important difference. These statues of the idealised human form were godlike and distant: we are not meant to identify with them but to aspire and wonder. And wonder we did, wandering between the statues and exploring them from every angle.

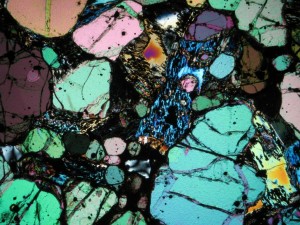

We were then treated to a private tour of the Sedgwick Museum which involved examining some myths and legends surrounding this awe-inspiring collection, and thinking about some of the ways into geology that make this erudite and seemingly inaccessible area exciting and available for even very young children. There was, for example, a story kit to tell children about Darwin’s adventures on HMS Beagle with a beautifully crafted blanket in all sorts of colours and textures with secret pockets containing coral, rocks and fossils for children to explore. We were also lucky enough to have the chance to speak to Matthew Hollis, the poet-in-residence at the Sedgwick Museum as part of the Thresholds project. He is yet another hugely inspiring figure and gave us some insight into another way of making connections. He spoke of the role of the poet in days gone by as a figure of great political and social importance, passing on ideas, weaving the stories we tell about ourselves and others (a role now shared with museum educators, it would seem). Matthew was also fascinated by the stories we tell about objects; the mythology surrounding the rocks and fossils in the Sedgwick Museum.

On Thursday evening I attended Matthew’s poetry reading at the museum and listened to his incredible poem, ‘The Stone Man’. I could not help but consider the poem itself as artefact, with its rich evocation of the weight of words, the physicality of printing technology, the design of the written word as an extension of our everyday speech. The tension between the artifice of purposeful poetic creation and the natural fluency of human speech was particularly powerful in the setting of the Sedgwick museum, surrounded by fossils and rocks with their own human stories to tell: the much discussed ‘real objects’.

Over the course of our four days at the Fitzwilliam we were able to observe a number of education sessions all of which facilitated children’s direct engagement with the collection, through questioning which encouraged close observation. Whilst the children demonstrated an obvious respect for the gallery educator’s expertise, they were also empowered to discover and unpack their own responses. A phrase used by one of the museum educators struck me in this regard, as she spoke of respecting the early years audience ‘as interpreters of art on their own terms’. She and others used storytelling as a familiar bridge to the unfamiliar. There was a palpable shift in emphasis: by literally putting their ideas first, before the presentation of any factual information about the artefact, the application of the children’s interpretative skill and the validation of their individual responses became the focus of the session: “anything they pick up about the ancient Greeks is a bonus!”

This persistent focus on empowering young audiences was consistent across the age range, including during a fantastic Widening Participation session for a group of Year 10s. Below is my attempt at an outline of Peter’s profile, drawn (without looking at the page) in one sculptural motion… You’ll have to take my word for it that it is an excellent likeness, if a little Neanderthal. The exercise was part of a wider exploration of identity in art which involved generating rules or conventions which appear to have guided expressions of reputation in ancient civilisations; iconography in Medieval and Renaissance religious art; and the human search for natural forms in abstract shapes in contemporary art.

Had Ian asked for their ideas about these subject areas, I would imagine he would be met with blank looks and shifting feet. As it was, he asked for first impressions and involved them with drawing activities on the gallery floor (surrounded by the artworks themselves) which unearthed a wealth of responses, connections and knowledge upon which to build, and encouraged these young people to consider themselves as artists and interpreters.

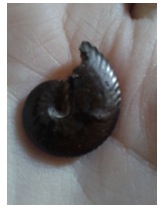

It is telling that the most powerful experience of all this week, for me, was being handed an 80 million year old ammonite of my very own. This tapped into that basic human instinct for collection which is shared by children and museum curators alike. I wrote a short rhyming story, ‘The Quiet Ammonite’, which I hope to use to encourage children’s curiosity about the world around them. I wrote holding the ammonite as my talisman (he’s an old hand at that sort of thing) and staring into the tiny spiral. This week has implications for my future practice and will no doubt lead to a shift in emphasis in my teaching as I continue to reflect. Above all, it has filled me with hope that the objects, poems and stories that I share with children in the future, in the classroom and in the museums of Cambridge and beyond, will leave them, as they leave me, ‘spiral-bound’.