Thin sections at the Sedgwick Museum

12th March 2013 | 0 Comment(s) | The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences

Matthew’s preliminary visit to the Sedgwick Museum a couple of weeks ago was a packed day which squeezed in a whistle-stop tour around the Museum and the Department of Earth Sciences from top to bottom, attic to basement, mass spectrometer to mammoth teeth. This project is all about revealing hidden things and looking at our collections in new ways, and one thing a geologist never loses fascination for is the transformation that rocks undergo when they are viewed through a microscope. So we took Matthew to visit Rob in the Sectioning Room, which is not as grim as it sounds. Rob is a craftsman – his job is to carefully turn samples of rock into analytical thin sections mounted on a glass slides. The rock slices are incredibly thin – he painstakingly grinds them down until they are just 30 microns thick, like a human hair – so that even the densest, blackest volcanic rocks become transparent and can be viewed through a petrological microscope to reveal their mineral composition and texture.

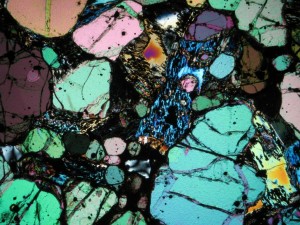

Petrological microscopes are specially designed for looking at rocks, and as well as viewing your thin section in either normal or filtered (also known as Plane Polarised) white light, you can also flip a switch called the Analyser. This inserts a second polariser which filters the light that has already been refracted by passing through the thin section before it reaches your eye. The result? You see a rainbow of interference colours, your black rock is suddenly transformed into glorious back-lit stained glass. Different minerals have different colours in cross polarised light because they bend the light coming through them by different amounts. For a petrologist this is important as the colour variations enable telling one mineral from another – which is very hard to do just from looking at a fine-grained black rock.

The development of this microscopy technique in the late 19th/ early 20th century quietly revolutionised the study of igneous and metamorphic rocks. As well as revealing what minerals a rock contained, thin sections allowed geologists to see for the first time how the crystals in a rock fitted together. This in turn gave them clues about which minerals crystallised first, leading to advances in our understanding of the complex processes taking place in magma chambers deep inside the Earth that lead to their formation.

We’re looking forward to introducing Matthew to our collections over the coming weeks, and seeing them through his eyes and his words.

The rock in the picture is a thin section made from one of the volcanic rock samples that Charles Darwin collected from Sant Iago, one of the Galapagos Islands, viewed through cross polarised light.

Annette Shelford, Museum Education Officer